Accounting vs Economic Reality Part 2: Intangibles

This is our second entry in a multi-part series on some of the common failings of GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) when it comes to truly understanding the economics of a business.

GAAP accounting is the accounting you will find if you open most US publicly reported financial statements. These are the numbers commonly used by the financial press to quickly access the financial health of a given company, and these are the numbers relied upon by quantitative models and many active managers to manage an ever-increasing portion of client’s money. However, these numbers do not always represent what is actually happening at a business.

In our last piece we talked about adjusting for stock-based compensation. Today, we will be talking about intangible asset adjustments, which are far more subjective and therefore far more difficult to correct for.

Going back to first principles; remember that what we are trying to accomplish with any accounting analysis is to decipher what the true economic cash flow generating ability of a business is for us as owners. This is an inherently difficult exercise despite all the shortcuts that Wall Street would have you believe, such as ‘style’, valuation multiples, accounting ratios etc.

In reality, to understand a business takes deep work as there are always many qualitative factors involved: the value-add of a product/service, industry trends, competitive moats, capital allocation decisions, and hundreds more. Accounting practices do not have the flexibility to capture the level of nuance it takes to really understand a business. Think of this another way- if you were going to buy a business to run yourself, you likely wouldn’t do so from afar based just on a spreadsheet. You’d want to meet the managers and the employees, walk the facilities, test the products, and understand the business behind the numbers.

To be clear, publicly reported accounting is often still a very good starting point in business analysis, but it is simply one of many difficult and complex things to include when it comes to truly understanding a business.

Intangible Assets

Intangible assets have grown in significance over the last two decades. In fact, you could make the case that the growth of intangibles (and the inherent difficulty in defining and valuing them) is one of the reasons many so called “value investors” (defined most often as those who seek to buy businesses at or below book value) have missed out on some of the best performing stocks of the past two decades.

Consider that in the past, the common way to grow a business was to invest in more equipment, buildings, and vehicles to enable you to produce more product to be sold. From an accounting perspective, all that investment would be recognized on the balance sheet of a business, which is called ‘capitalizing’ the assets (Balance Sheet: Property, Plants, and Equipment). Over time, the value would decline as the assets aged and became less useful and this depreciation was recorded as an expense (Income Statement: D&A expense). In other words, by capitalizing the assets on their balance sheet, the company was recognizing that it had invested in productive assets that would generate returns into the future and also recognizing that those assets have a finite life and degrade over time.

But today, more and more companies grow their business without the need for this traditional investment in tangible goods – instead they need to invest in “intangible” goods such as the software developed by a team of engineers. Think of examples like Facebook and Amazon – these are companies where the value of these huge organizations exists far more in their software and capabilities than in any hard assets.

For these “tangible-asset light” businesses, they typically create these intangible assets through their investments in R&D (Research & Development), a cost which is most commonly fully expensed in the year that it occurs (Income Statement: SG&A Expense), and crucially there is no corresponding asset added to the balance sheet. Put simply, if a company develops a powerful new piece of software it records the development expense and cost of creation in year 1, but does not recognize that any asset exists, even though it may generate revenue for many years.

So you can see that there is a significant accounting difference between tangible and intangible investments, despite both ultimately being long-duration investment assets in real terms. In short, tangible assets are accounted for on an accrual basis, whilst intangibles are accounted for on a cash basis.

We would add here that IFRS accounting rules do currently allow for the capitalization of certain intangible investments/ assets, provided they fulfill set criteria. Such flexibility is not currently afforded under GAAP, which is where the majority of our companies sit so is where we will focus our attention for this article. (Note: there is currently pending legislation to amend GAAP and allow R&D expenses to be capitalized and then amortized over a five-year period. This legislation is slated to come into force during 2022, but there is some debate around it, and we will need to wait and see if and when it actually appears in reality)

To return to the core issue, this discrepancy in accounting treatment between tangible and intangible investments creates a problem when it comes to relying on reported numbers to understand a business. This problem is realized in two very different ways depending on the life-stage the company is in.

Firstly, for those businesses in growth mode who are continually investing and creating new intangible assets, the effects are the following:

- Understated Earnings (due to higher expenses in current year)

- Understated Book Value (due to lack of tangible assets on the balance sheet)

- Understated Invested Capital (due to lack of tangible invested capital)

- Overstated Return on Invested Capital (returns look high because the invested capital base is understated)

So, to get to the real economics of these businesses we would need to manually capitalize appropriate expenses SG&A (selling, general and administrative) that are creating future intangible assets and include those on the balance sheet. Those intangibles would then need to be amortized over time (amortization is simply the term for depreciation for intangible assets).

Note we said ‘appropriate’ expenses. This is where we begin to run into one of the main reasons that accounting practices don’t cope with intangibles well, and why most asset managers don’t either. There are two serious problems:

- It is incredibly difficult to determine exactly how much of a company’s SG&A budget is in fact going to create long term assets. It is entirely subjective. After all, by their very nature these assets are neither easy to identify nor easy to value. We often do not have sufficient disclosures from the companies when it comes to their SG&A or their R&D expenses in order to determine how much of the annual spend is really creating assets.

- Secondly, even if we did have that information, it’s then extremely difficult to accurately ascribe a numerical value to the asset being created. Just because a firm spent $1M on software development for a new platform doesn’t mean they’ve created a $1M asset. It could be worth far more, or far less than that. (We could write a lot more on the variety of ways that such assets could be theoretically valued, but that’s likely not helpful).

While most analysts do not want to make these judgements because they are so inherently subjective, we will always get a far better understanding of the actual underlying economics of a business itself by at least making an effort to adjust for these issues (as always- it’s better to be vaguely right than precisely wrong). And the more we study a business, the more likely our adjustments will be correct.

The second situation to consider here is a company that is no longer in a growth phase, and no longer investing in creating new intangible assets. For these more mature businesses, they may now be generating significant earnings based on R&D spent years ago.

In this case, the company is generating returns from an asset not recognized anywhere on their balance sheet (once again, their ROIC will be inflated as a result), and in addition, they won’t be recognizing any amortization of these intangible assets. In effect, we find ourselves in scenario where now profitability might be being over-stated, whereas it was previously under-stated. We see this result in a number of older technology companies that might have spent too much time harvesting what they built in the past than investing in the future (Nokia, Blackberry, and possibly even Microsoft before the turnaround under Nadella).

There is one final nuance to be aware of with all of this. If intangible assets are acquired through a business purchase rather than being internally generated, then the buying firm is required to ascribe an approximate value to the intangible assets, and that value will then sit on their balance sheet and be amortized. This point is important to note when looking at companies that have grown in different ways – companies that have grown through acquisition will likely display and recognize significant intangibles on their balance sheet. Those companies who have grown organically and created their own intangible assets internally will show little in the way of balance sheet assets. In reality, the two companies may have very similar assets, but their accounting statements, ratios, and profile will look very different. Another great example of the danger of relying on quantitative investing, stock screens, or ratios in isolation.

Examples

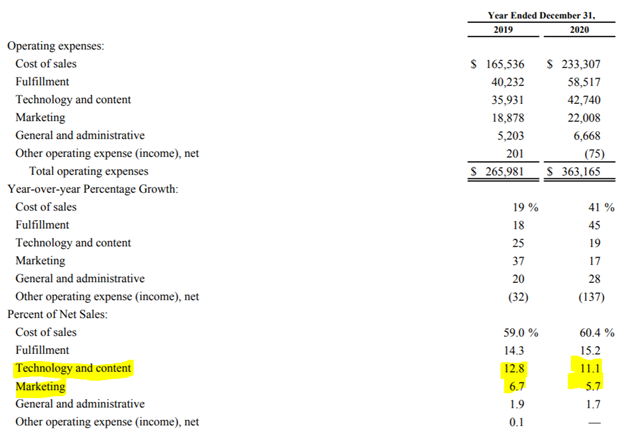

Consider Amazon’s 2020 reported operating expenses:

Now without going into each of the line item in detail, we can safely assume that at least a portion of the expense related to technology and content, and to a lesser extent customer acquisition costs in marketing, is in reality creating intangible assets that will support future profitability. For example, think of the software platforms being created around AWS (Amazon Web Services), or the original programming being created in Amazon Prime, or think of the investments made in Alexa Voice OS, or in building out their Advertising platform. In each case, Amazon will reap benefits from these investments for years into the future.

We see something similar at Facebook – the company is currently employing 10K+ full-time engineers to build out the intellectual property for VR/AR which currently produces next to nil revenue but is a huge cost in their operating expenses (not broken out as cleanly as Amazon) and does not feature on their balance sheet in their assets. Anyone taking a superficial view of the accounting or relying on traditional ratios would conclude that core FB margins are a lot lower than they actually are, and the balance sheet more levered than it really is. And VR/AR is just one of a number of such examples that muddy the current Facebook financials.

Conclusion

We will not profess to have an easy fix for those in the un-enviable position of having to set accounting rules, but we instead want to simply make investors more aware of how and why they may be misled by accounting numbers and ratios if taken at face value. The main thing that matters in the end is always going to be the true underlying economics of the business. Getting to that is always the goal.

Companies like Amazon and Facebook will continue to trade up and down based on reported GAAP numbers. Stocks will continue to be bought and sold based on ratios, and included in portfolios based on screens, quantitative factors, and other such misguided methodologies. But all those who invest money based on numbers that do not represent the actual businesses are taking a significant risk. For the genuine investor who focusses on understanding the real economic reality a company, this will only provide more opportunities to buy undervalued shares.

Disclosures: This website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to provide advisory or other services by GCI Investors in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. The information contained on this website should not be construed as financial or investment advice on any subject matter and statements contained herein are the opinions of GCI Investors and are not to be construed as guarantees, warranties or predictions of future events, portfolio allocations, portfolio results, investment returns, or other outcomes. Viewers of this website should not assume that all recommendations will be profitable, or that future investment and/or portfolio performance will be profitable or favorable. GCI Investors expressly disclaims all liability in respect to actions taken based on any or all of the information on this website.

There are links to third-party websites on the internet contained in this website. We provide these links because we believe these websites contain information that might be useful, interesting and or helpful to your professional activities. GCI Investors has no affiliation or agreement with any linked website. The fact that we provide links to these websites does not mean that we endorse the owner or operator of the respective website or any products or services offered through these sites. We cannot and do not review or endorse or approve the information in these websites, nor does GCI Investors warrant that a linked site will be free of computer viruses or other harmful code that can impact your computer or other web-access device. The linked sites are not under the control of GCI Investors, and we are not responsible for the contents of any linked site or any link contained in a linked site. By using this web site to search for or link to another site, you agree and understand that such use is at your own risk.