Most of us have a basic understanding that the future is uncertain. Maybe the stock market will crash tomorrow or maybe a war will break out somewhere. We know that more things can happen tomorrow than will. However, when we look back at yesterday, all we tend to see is certainty. We see the events that happened, and we assume that they were the only events that could have ever happened. In hindsight, everything seems obvious and we construct explanations post hoc for why it was obvious. Over time, this backward sense-making starts to filter into how we see the future.

An event could have been completely random, but we will still try and construct a reason for why it happened. This tendency – to find patterns where none exist – is ingrained in our nature. If that swaying grass turned out to be a lion, and our ancestors didn’t run, it would have been game over for them. However, in today’s world, that mechanism of overconfident prediction often gets us into more trouble than it is worth. The roulette wheel landed on red 5 times in a row, black is guaranteed. The price of oil keeps dropping, it is due to go up. Pattern X will lead to outcome Y since it has in the past.

A whole industry of TV commentators and sell side analysts have been built up to take advantage of this inherent unwillingness of humans to accept uncertainty. Unfortunately, these modern-day forecasters are often no more useful than the soothsayers and oracles that came before them.

Today we will discuss why the TV commentators get it so wrong, why the sell-side focuses too much on quarterly numbers, the short-term mispricing this creates, and how we as long-term investors can take advantage of this.

Financial Journalism: Follow the Incentives

In 2003, back when Saddam Hussein was captured in Iraq, Bloomberg News released the following headline: TREASURIES RISE; HUSSEIN CAPTURE MAY NOT CURB TERRORISM. About 30 minutes later, they released another headline: TREASURIES FALL; HUSSEIN CAPTURE BOOSTS ALLURE OF RISKY ASSETS.

This contradiction was made famous by Nassim Taleb in his book The Black Swan. Obviously, two opposite consequences can’t be explained by the same thing, but that rarely stops a good story from being published. Similar examples are littered throughout the financial news landscape, and it’s not just backward-looking stories.

If the question is when markets will recover, a first-pass answer is never. Under any circumstances, putting an irresponsible, ignorant man who takes his advice from all the wrong people in charge of the nation with the world’s most important economy would be very bad news. What makes it especially bad right now, however, is the fundamentally fragile state much of the world is still in, eight years after the great financial crisis.

Since then, the S&P 500 has risen more than 30% (Krugman would later retract this prediction as an emotional lapse in judgment). The point of this example isn’t to pick on Mr. Krugman, but to point out that even the most world-renowned authorities on the economy often get prediction very wrong.

So, if prediction is nearly impossible to get right, then why does it feel like every time we turn on CNBC there is a pundit telling us exactly what will happen in the next three months? Basically, if there is a market for something, someone will supply it, and there happens to be a huge market for predictions. This demand incentivizes pundits to continue making those predictions whether or not they are accurate, and lucky for them, most people quickly forget their wrong predictions, and remember their right predictions. As the saying goes, even a broken clock is right twice a day.

Wall Street and Short-Termism

In the same way TV pundits sell short-term predictions to retail investors, wall street sell-side analysts sell short-term predictions to institutional investors. Again, if there is a demand for a product, someone will supply it, regardless of its efficacy.

For an example, remember back to the depths of the great recession. There was no shortage of Wall Street analysts slashing their earnings estimates as the crisis unfolded. The thinking was things were bad last month, so things would be bad next month. This short-term mindset was rampant, and it got to the point where wall street analysts were putting price targets on American businesses, with long histories of consistent earnings, that assumed they would never be profitable again. There was a complete disregard for the long-term outlook.

For a more recent example of this short-term mindset, look at what happened with Facebook this past quarter. The company announced a cut to their one-year forward guidance, causing a wave of Wall Street analysts to cut their targets on the company, which led to a 20% market sell down in the stock. Just like during the recession, the market focused on the short-term and forgot that businesses generally operate over decades in which time they produce the bulk of their shareholder value.

There is a very good reason why Wall Street in particular takes such a short-term view on investing – trading commissions. Many banks and research houses still make the majority of their money from trading commissions. As a result, they need their analysts to continually change views on stocks, to make sure clients keep buying and selling them. Long-term investors, such as us, are terrible clients for Wall street brokers. Investors who do serious research and then buy and hold stocks for a long period of time, without continually buying and selling, do not pay much trading commissions.

The Great Advantage of this Short-Termism: Asset Mispricing

As more and more investors avoid doing the hard work for themselves and instead defer to the judgement of short-term oriented, sensationalist TV pundits and Wall Street analysts, opportunity is created for long-term investors who are willing to do the work and take a firm view on an investment. For example, during the last recession, great businesses were being sold for pennies on the dollar and investors who stepped in to buy with a long-term mindset ended up doing exceptionally well. The same will likely be true with the Facebook example (and is the reason we chose to buy more after the fall).

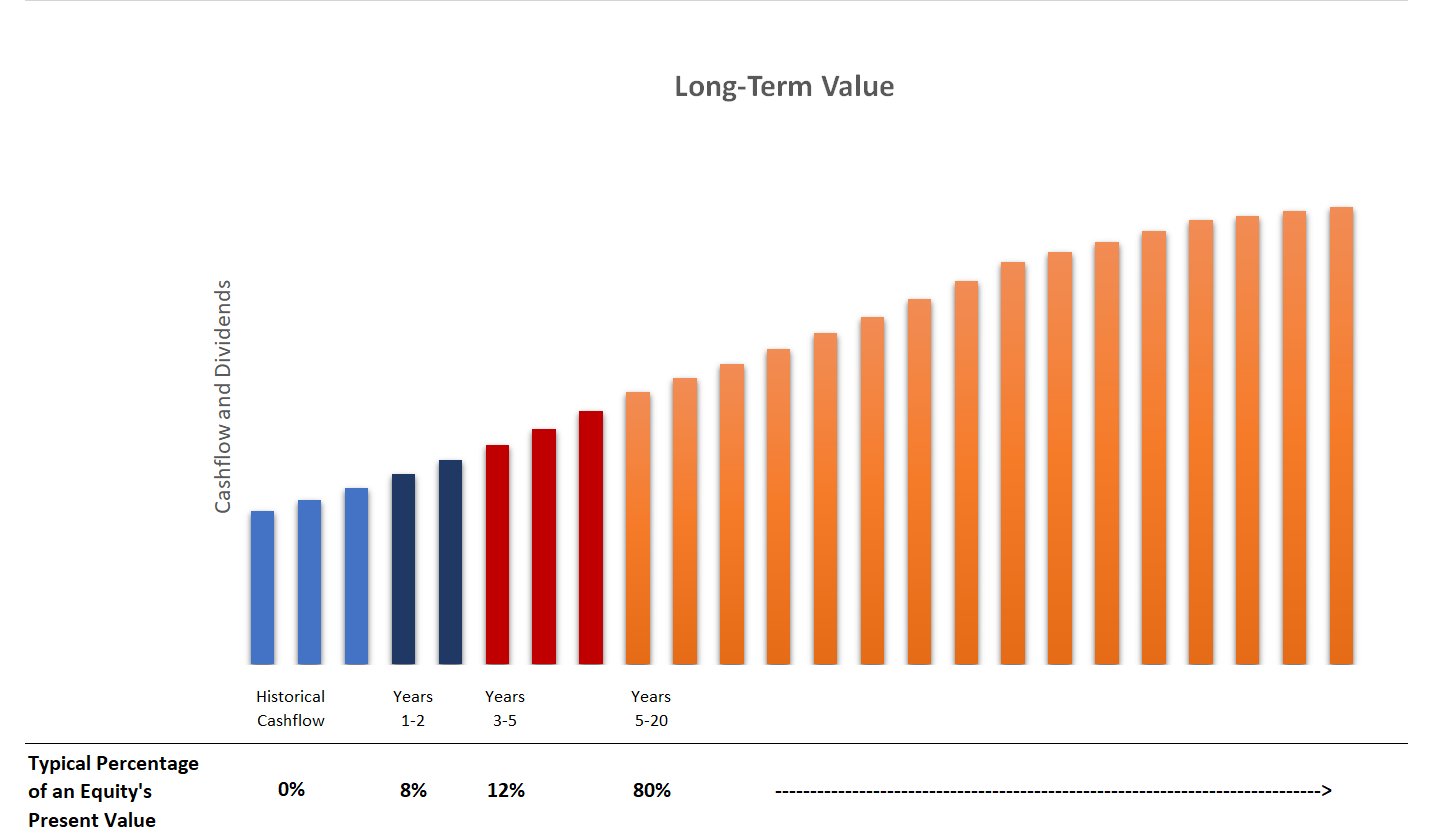

The reason long-term investing consistently works is that most of the value in a company lies much farther out than the next one to three years (which is as far as the sell side tends to go).

Fundamentally, the value of a company is determined by all the future cash flows that the company will generate over its life, and the share price simply represents how much investors are prepared to pay for those cash flows today. When one breaks down this total valuation over time, it becomes very clear that most of the value of a company lies further out. Consider the following graph: